A BOLD BRAZEN SERPENT

a colonial and post colonial romance; a voyage around my father

Sydney Uni circa 1935 John Arthur McKelvey Shera back row fifth from left

Dear L, Dear T,

Dear G, Dear B; Dear D

Dear F, and A, C, and E;

My Dear readers; Mes Chers lecteurs;

My dear Jibbidy F and A C E, as my mother and sister used call me in more formal addresses to my complex puzzle ; or shortened to just Jibbidy when they found me curious or looking for something to eat.

Regarding our alignment in previous orbits; maybe it began in the earliest years of the 20th Century when my grandmother, as the jeune fille Alice Pfitzenmaier, was the dux of Kinkoppal Sacre Coeur Convent, Rose Bay, in Sydney, New South Wales.

Alice’s family were Flemish and spoke only French at the dinner table and built great colonial and public houses in the North of Australia. My mother recorded they had “left Europe to escape Bismark’s conscription” in the 1860s.

Alice would have travelled to Sydney from Rockhampton via ship or rail to enjoy her education at Kincoppal. Her father, Louis, who was born in Stuttgart had travelled through Queensland by bullock dray

through a land still riven by violent possession and dispossession.

Alice told a story to her grandchildren that once, while travelling with his family on drays, Louis’ family were stopped by fierce aboriginal warriors. The warriors took an interest in the wailing, strawberry-blonde, teething baby of their party. The baby wore a red scarf around her jaw as a remedy to her pain. The child’s aboriginal nanny in the Pfitzenmaier party told the warriors to go away and not to touch her “boodgerie white Mary”. And so Pfitzenmaier’s party were let pass by the warriors who took with them only the red scarf from the crying baby.

Zilzie Beach and Mother Macgregor Island

Perhaps dear A, our family’s orbits crossed some fifty or so years later; during World War 1.

Despite Australia’s recently formed federal government’s desires, the Pfitzenmaier family avoided Internment because of their location in their friend the Labor Premier T.J. Ryan’s anti-conscriptionist Queensland.

The emergent Labor politics of Queensland was divergent and far away from the politics of imperially aligned patriotism that saw the new nation give so many so freely to be slaughtered in Europe and the Dardanelles.

Louis was told “it was the federal government’s desire to intern him” but the local federal representative told him that they knew Louis was “a good bloke” and that if he just phoned the local police station each fortnight that would be sufficient.

From their grand house, laden with red cedar furniture in that antipodean town not far from one of the world’s great gold mines at Mt Morgan, in lands of plentiful meat and the golden fleece, the good Flemish family sat on chairs that would last into their second and third centuries. The family would profess, elegantly and skilfully, that they were neither German nor Jewish. Even though some others in the land of the kangaroo and emu had claimed they were both or either.

Germany as a nation state did not exist when Louis had left Europe in 1864. Rene Descartes had been dead for two hundred years, Captain Cook for about 90 and Napoleon Bonaparte had been dead for 40 odd.

Around 1905 or 1907 Alice Pfitzenmaier it seemed had been swept off her feet by a red blooded ozzie boy, Percy Berry. Percy was an early Australian sporting god and a descendent of one Captain Berry whose family had gone into the sugar business in the colony of New South Wales and Queensland. She had probably met Percy on the ship plying from Sydney to her great home in the Tropical North when both were returning with their respective triumphs, hers in education, and his in sport. In 1907, after one of his many triumphs at the Australasian cycling championships, the good citizens of Brisbane built a special track for him at the Gabba to attempt a world record. A year after in America Henry Ford developed the Model T Ford. In December 1903 the american bicycle retailers Orville and Wilbur Wright had announced their first powered airplane flight in distances of less than 100 metres at Kittyhawk in North Carolina. Australia had become a federation of States for less than a decade.

Mary Rebecca “Rae” Berry

Percy later retired from sport to move into the liquor business and run the Union Hotel, possibly leaving Alice to regret each day her loss of the gentility of her fast diminishing European family and the sweet songs of her brother Frank a tailor and singer of renown who had long since high-tailed it south but died an early death from consumption; tuberculosis.

It was said that Harry Van der Sluys, or Roy Rene, who was also known by his stage name as the irreverent Mo Mackacky, preferred to stay at the salubrious Pfitzenmaier hotels. Off stage, out of person Harry was known by the Pfitzenmaiers as a perfect gentleman.

Alice also told her daughter Rae that the redoubtable bookmaker and political fixer of Melbourne John Wren was a very nice man. John Wren must have valued the company of a bike racer who could swoop down from the North and beat the field with aplomb. Both would also have realised at that time that , unlike themselves, a preserve of the Australian ruling class, the exclusive Melbourne Club of 36 Collins St, did not admit Catholics or women and the gambles of the working class.

The Depression, children seconded to the Second World War, and the post war baby boom followed in the life of Alice Berry nee Pfitzenmaier. I’m sure our orbits passed near by then dear A, although neither of us was born at that time.

It was in 1946, still in his army uniform, that my father had married Mrs Alice Berry nee Pfitzenmaier’s daughter “Rae” also known as Mary Rebecca Berry. Of course in those days Mrs Alice Berry would be referred to as Mrs Percy Berry. And so began Alice’s further fall from the lofty spires of Kinkoppal and Europe and into the world of the bold brazen serpents of Australia.

Then came the increasingly affluent 1950s, 60s and 70s; and this is the bit where you and I come into the story A; when we became players in our families' stories. In the 1950s, I was a howling baby and a difficult infant, I’d even been hit over the head with the school bell by Sister Mary Ultan after exhibiting one of my unalloyed rages.

Did I see you on a holiday at the seaside at Surfers Paradise, Kirra, Coolangatta, Burleigh Heads or Tugan, at this time? I cannot recall. I was too young at this time.

Cambridge Lodge Surfers Paradise circa 1967

My mother and father bought a unit in a place called Cambridge Lodge in Surfers Paradise in the late 1960s and at this time began Alice’s great misfortune.

Her husband died early through misadventure. Possibly confounded by diabetes and alcohol and a faulty ticker; he drowned in the surf.

And so Alice, Mrs Berry, nee Pfitzenmaier came to live with us in a suite which my dad and mum had built at the southern end of our grand old Queenslander.

My father plied his trade as the good doctor to the salt of the earth in the industrial city of Ipswich. His huge house surrounded by trees and verandahs next door to one of the hospitals in the town was bought with a war service loan. Brisbane was close enough for Rae to see performances by the Queensland and even the Royal Ballet and close enough for most of the children to go to University by motor car.

The good doctor’s house was occupied by my father, my mother, my sister, myself and my five brothers and our two dogs; two short haired golden labradors. It was close to the hospitals where my father delivered hundreds of children and performed tonsillectomies and appendectomies and so on and so forth. It was near the Zoo and Municipal Park in the industrial city of Ipswich.

The Town Hall clock would ring out the hours and my father would be on call day and night with each of the children instructed how to answer the phone should a patient call and my father or mother not be home. If my father did have a new call he had to attend to while he was out on call, we would turn a light on, on the verandah at the front of the house, so he knew not to park under the house.

Dr John Shera and nursing staff 1940 or 1950

While Alice’s husband Percy the publican and sports star was a great provisioner to a hungry town of strong men with great thirsts at his Union Hotel, in Rockhampton, my father John had inherited from his maternal uncle, the surgeon, a dogged vocation of service to the ill, gravid and infirm no matter what their stripe, creed, colour or calling.

7 of Alice Pfitzenmaier’s grandchildren 2 dogs plus one son -in-law at Emu Park circa 1964

Possibly Alice’s heart had hardened with the loss of “her life” as she became a prisoner in the house of her oldest daughter and son-in-law and their seven, irrepressible, ungovernable, unbearable children and her son-in-law’s much loved canines.

Perhaps it was the loss of her gentle, cultured European father and gentle brother and her experiences with the less genteel in the alcohol economy of her husband’s business, into which trade her only son had followed, that had made Alice bitter.

She would call me, one of her 16 grandchildren, a “bold brazen serpent”. Collectively my five brothers and I bore a less biblical invective as “ a pack of savages".

I’m unsure as to why there seemed an animosity between myself and my maternal grandmother; I’d never met her husband, my maternal grandfather or my paternal grandparents for that matter; they had deceased before I was born.

Perhaps it was my proclivity for rage that reminded her of her spouse who had also been over-endowed in the testosterone department; perhaps it was my savagery. I cant remember, as an infant, hitting my older brother Michael over the back of the head with a “four by two” one day when he was intently playing with matches or fashioning some lead sinkers under the house.

Maybe he had dissed me and didn’t let me indulge in this incendiary adventure with him and I took it upon myself, as a pre-verbal infant, to express my unexpected but savage revenge at my dismissal from all that fun.

Maybe my only living grand-parent wanted to protect my younger siblings from me and my killer’s ways. Maybe it was my riot of disrespectful friends from along the street who made her life less than peaceful.

I do remember being angry with her, and she with me, when she did not let me play the Caruso record on her wind up gramophone for my childhood friend and fellow thespian Harry Gibbs and our dear younger friend Johnny Burke and any other younger siblings who would tag along in our little gang as we trawled from one family house to the next in search for a good time. My grandmother said I’d worn out all her needles on her gramophone and they were expensive things to replace.

As twelve year olds my friend Harry and I had wanted to do a performance “A night at the Opera” for the neighbourhood pantomime and re-enact a scene in Caruso’s life where a blood vessel in Caruso’s throat ruptures during a performance. Harry and I loved melodrama!

And we desperately wanted to rob my grandmother’s vault for the vital soundtrack.

I also recall, one horrible day, when some kids had discovered her collection of hard, black shellac 78rpm records in storage under the house near the dog kennel and they set about breaking each one on the cats-claw laden fence next to the “Snakes’ Yard” with the joyful cry “I broke a record!” Perhaps I was, like my friends Luke Gilmore Wilson, and our mutual friend Harry from down the street, just a “terrible child”; and so my grandmother and I did not get on.

Later I would ritually visit my grandmother in the hospital next door as she failed to recover from a broken hip and other maladies. It was one of my duties, after walking home from school. After that I was allowed to hoe into an afternoon tea of fresh bread and raspberry jam. Some days even my dear but annoying friends accompanied me in this daily ritual.

My father had been born in the outback railway town of Alpha in central Queensland in 1913 and was a student of medicine at Sydney Uni in the 1930s where his Uncle was a lecturer in surgery.

Now here is another possible collision between my clan and your’s, dear A.

My father’s uncle, his mother’s brother, Sir John McKelvey, was a surgeon and lecturer in surgery at Sydney University and a resident of Tusculum St, Potts Point in the 1920s and 30s.

After work as the superintendent at the Alfred Hospital in Melbourne he had become a teacher and practitioner at Sydney University and a number of Sydney hospitals including St Vincent’s and Lewisham in South Sydney. It seems he was one of the Australian PM Jim Scullin, and the NSW Premier Jack Lang’s ozzie Knights of the Realm. He also had an interest in the breeding of horses.

Following Sir John’s death in 1936 it was stated, among other tributes in the Sydney Morning Herald that this great surgical benefactor would be “sorely missed by the sick poor of Sydney”. My father John was named as one of his principal mourners at his rather large funeral.

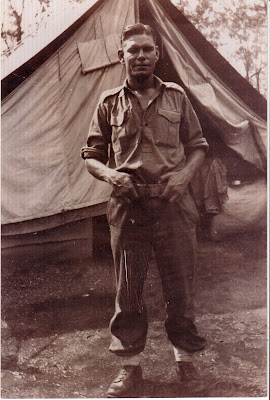

1946 saw the end of his nephew John Shera’s service with the Australian army having been one its doctors and a Captain during WW2 on the Kokoda Trail, and among other places, at Sananda, Finchhaven, Tarakan and Gona.

After being first conscripted then re-enlisting, he finished his war, if he could ever finish it, on the island of Morotai where the Japanese Second Army surrendered. He remembered no great rejoicing at this time, just relief that it was all over, and an aching desire to go home. He had seen enough mutilation of human flesh, of every colour in the immense cruelty that is war.

And so in 1946 in his army green uniform, Captain John Arthur Mckelvey Shera, took the hand in marriage of Mary Rebecca “Rae” Berry.

John was a Sydney University graduate; decorated “for exceptional devotion to duty under fire” during the Kokoda-Owen Stanley Campaign and having given “immediate assistance to the wounded and attending to a long series of battle casualties over days and nights at Isurava, Gona Mission and Gona village”. He was also a veteran of battles at Finchhaven, and Tarakan; the nephew of the late Sir John McKelvey of Sydney University. He was the son of the American born Irish-Australian railway man, Arthur Shera and Arthur’s late wife Mary Ellen McKelvey.

“Rae” was the daughter of Alice Pfitzenmaier and Percy Berry and had worked for a short time in the office of the fledgling government broadcaster the Australian Broadcasting Commission in the city of Sydney.

After eight years of marriage, and four children, and as Doctor John Arthur McKelvey Shera M.B.E., as his name plate stated in the city of Ipswich, I was born, the first of three further children born in that town.

Later he built a modern medical clinic in South Street in Ipswich with plans from his Sydney Uni architect friend Martin “Bill” Conrad. There was even a little x ray machine at the clinic that the rugby league footballers, of which the town was renowned, could be examined. He and his colleague Dr Kevin Brennan gave me a job there as a 14 year old mowing the lawn and tending to the garden.

Perhaps you remember him dear A? When you came to our old house while touring the land with one of your wonderful musical ensembles. I remember you had tonsillitis and he treated you with care and attention. I think he liked you.

Maybe as a boy too young to remember I’d been over to your mum and dad’s house, or a holiday house on the coast, a house of girls and dancing and dressing up and hi fi music. Or maybe you were at one of those theatrical workshops organised by Mrs Uletta Patterson and led by the wonderful actor Mr Murray Foy. I remember learning a waltz with a girl there, who I thought was the most beautiful girl in the world with the softest midriff zone unlike any of my five brothers or sporting friends. O where oh where did she go? The theatre workshop de-camped and we never met again at least in this world. I think her name was Solveig.

But back to my father, that taciturn, brown skinned gentleman born on the railway line in Alpha central western Queensland; he was a man as committed and preoccupied as his uncle to the provision of medical assistance to any man, woman or child.

How lucky he was to have married his Rose of Tralee the beautiful, vivacious, intelligent, fair voiced Mary “Rae” Berry, daughter of Alice and Percy! A happy woman who was a good sport and who also loved to sing along to the arias of Verdi, Pucccini and Gilbert and Sullivan.

To be fair to my father, as an eminently eligible suitor, he did take the French, English and History prizes away from the Pattersons, the Archers and Kellows when forced to finish his secondary education with the heathens and Protestants at the Rockhampton Grammar School. And he had cleaned up a few of them up on the cricket and football fields; mixing with ease with his fellow sports tragics, the Kelsos, the Lavers, the Loanes, and the Windsors in those fields where an indomitable will was a prime asset.

He was also a man of great intellect who was driven by an irrepressible determination. He also had a passion for learning. Blessed by the gods he also had the gift of excellent hand and eye co-ordination. And he was afraid of no one. He had earned the respect of the European elders among the Pfitzenmaier family and of his father-in law P.S. Berry.

Perhaps it was not such a surprising match after all.

Despite the perfect marriage, my mother told me that, when the pair were first married, my father, not long back from the war, would wake in her arms in the middle of the night screaming with a nightmare; still stalked by the atrocity of War. Then the first thing he would reach for in the morning, when his eyes opened, was a cigarette.

Well then, there they are, finally married; John who was his own master and the vivacious Miss Rae Berry the daughter of the sometimes haughty Alice Pfitzenmaier, and Percy the publican and sports star.

Rae was the grand-daughter of the great immigrant and self made man Louis.

John was the Australian grandson of an irish american railroad man who had been fed up with Ireland and its subjugation and fighting, and who had also been fed up with the fighting in America. He was also the son of Arthur and the mysterious Mary Ellen McKelvey who had been married previously before marrying Arthur.

During their romance Rae had been chaperoned on her dates with John on beautiful Zilzee beach by a tippling auntie, a relative of the late Premier Ryan who had prized education and had struck a medal for the best academic student in the State and who later became Treasurer of Australia before being struck down at an early age by Spanish flu.

letter from Army camp in Tarakan to Miss R Berry, Union Hotel Rockhampton

For many years each summer school holidays my mum and dad would bundle all their children into the car, a Dodge Phoenix or a Chrysler Royal, and leave before dawn to pilgrim back the 500 miles to the Capricorn Coast where my father would swim like a dugong or a dolphin with we kids joyous on his back.

We would visit his brother Jim, whose wife had died in child-birth, and his sisters Margaret and Mollie. His sister Betty was a Matron at Fermoy Hospital in the South and sometimes she was there too. His brother Stanley “Snowy” who had also been a soldier had died not long after my parents’ marriage and the end of the war. He ended his days in a mental asylum dead in the same year as his father.

My mother would catch up with her brother and his children and some other cousins. Dad would also catch up with some old doctor colleagues there. And we kids would name the islands as we walked the beaches and played on the rocks amid the beach de mere and periwinkles.

After we passed through the city of Rockhampton and approached our fabled holiday town of Emu Park with its huge stuffed crocodile adorning the exterior wall of its beachside hotel we heard the terrible story of the Darumbal people herded up, shot and thrown over the cliff’s edge on one of the low mountains that watched out towards the sea.

An act of savage and filthy genocide in a time past where the indigenous people were comprehensively robbed of their land, their language, their food sources, their lives and their cultural practices in the dirty undeclared war that was the march of colonisation.

We cheered when we were told the story of the aboriginal people who attacked the cruel squatter’s house who had laced arsenic into their flour. Our loudest cheer was the moment in the story when, after approaching the homestead with spears hidden in the long grass and carried between their toes, our aboriginal heroes took up the spears and exacted their revenge on the cruel squatter bloke!

You and I are old now ourselves, dear A. But here is another memory from our world of home, where you know you are always welcome and the world of my dear dad for whom I know you had, like me, a deep affection.

In the early 1970s, at a congress of doctors in the town apprehensive about P.M Whitlam’s universal health care revolution Medibank, my father, an elder in the medical fraternity and a supporter of the plan, stated cannily that he was looking forward to the scheme as it meant that the 33% of his patients who he’d had to write off as bad debts would now be able to deliver to him recompense whenever they came to see him. My father knew how to dangle the carrot as well as the stick.

Throughout his life his children and their friends had perceived him as a severe man who was very strict and would truck no stupid ideas, whingeing or bad behaviour.

He governed with just a few rules: Respect for your mother, Respect for women and Respect for children, Respect for your fellow man and Respect and Care for the sick and ill, Refrain from stupid ideas, Don’t play with matches and Keep the house neat and tidy.

Inside his great brain was a closet of private memories to which he alone held the key. Memories that he might open in private and to himself while out of view on the golf course, asleep or watering the garden.

His children flinched at his flinty, war-scorched exterior and his exacting standards and his apparent distemper, but somehow I’d found a key to his inner peace.

I think it was making him cups of milk coffee in the evening as he watched T.V. Ringside on the television. Or laughing at the characters from the Mavis Bramston show, Hancock’s Half Hour or Dad’s Army. Or helping him watch the golf, cricket and rugby league; sometimes even in the middle of the night when it was broadcast live from England when everyone else was sleeping.

He would even take me out to the golf course with him where, after he had given up attempting to show me how to hit the white dimpled ball, I would help him locate his mighty and savagely hit balls that he would send out into the distance, usually with the slightest of fades to the right. I also liked to go with him to the Gold Coast and eat the mud crab ritually picked up from the street side vendor before as we crossed the mudflats on our way to the Coast.

My older siblings did not like the Gold Coast or golf as much as myself and my dad; but then they didn’t have the bourgie mates I had who were holed up with their medico parents in various apartments along the beach. And I suspect they were not so keen on spending too much time with my dear, but severe, old father whose anger had in their childhood still not mellowed after his close witness to the waste and barbarities of war.

Maybe he appreciated and was slightly amused that I was someone undoubtably burdened with a fight rather than flight set of genetic responses; that could be somewhere, somehow useful in some unlikely circumstance; and rise to the challenge in the event of being faced with a mad or irrational maniac intent on violence running at him or another with a gun, a club, a bayonet or a knife. Maybe he just appreciated that I shared with him his insomniac service to births, deaths and traumas and, on the holy days, cricket broadcasts from the Old Dart. Maybe he just liked the fact that I could laugh and sang songs with the untroubled voice of a sailor censored only by the deafening sound of a pounding sea. Maybe he just admired my mad determination to tackle anything that moved on the rugby league field.

It is 1997, not long after the death of my mother, John’s wife “Rae”; a vivacious, intelligent Mother of Seven, book-keeper, interior designer; educationalist; golfer, potter and lover of fine music; and and all hours receptionist for the good but taciturn Doctor. it is about 30 years after the death of Rae’s mother Alice, the good doctor’s mother-in-law, in the hospital next door; a small hospital in which the good doctor had been both a worker and a shareholder.

Confounded by a stroke some three years before, my father was hemiplegic; but our awkward bonhomie near the t.v. screen continued. After lifting him out of his nursing home bed and putting him in his wheel-chair and rolling him across a little park and up into his grand old Queenslander bought with a war service loan, the good doctor, some 84 years old, enjoyed the pleasure of his home thrones and a fine home cooked vietnamese meal courtesy of my wife his new daughter-in-law.

My wife was from a good Vietnamese family adherent to a respect for the ancestors, which in her case, as in mine, also had its fair share of soldiers, patriots and intellectuals; the plum-pudding of our respective heritages.

My wife’s mother’s family had been hanging round at the Hanoi University for the last 3000 years. Her father was a good old nationalist boy from the south whose father’s house had been burned down by the Diemists and his sister and Aunt had been imprisoned for their relationships with the Viet Cong and Viet Minh. My wife’s father was, like my father, a former soldier and bore that same severe visage. He had studied rocketry with the Russians and spoke Russian, Vietnamese and Chinese. I remember him laughing round an open fire in a paddy field west of Nha Trang when his cousin who was a few years older than he rattled off the French declensions. Declensions which he was spared from having to learn to perfection.

But on this particular day in 1997 I’d lifted my father from his bed in the nursing home onto his wheel-chair and wheeled him the sixty odd metres to his own bedroom in his own home. This was something my brother Peter and I did on alternate days for some 4 years.

He’d had a stroke at home some four years before while drinking red wine and eating my mother’s beef bourguignon at the formal rosewood dining table in the dining room that had been off limits for we children. At this dinner party he was in his own home enjoying the company of his wife, two other doctors and their partners, and a chemist and his wife.

The doctors immediately bundled him over to the hospital next door where he was placed in an induced coma. A few days later, he would wake in a makeshift ward in the local General Hospital a little further down the street with a view to the doorway of a room that he himself had occupied some forty years before when he was the Superintendent at the hospital.

Over the years following his stroke, he was relieved of the burden of responsibility and rectitude which he had always carried with him. He would uncharacteristically laugh when three of his six sons would struggle to put his shirt upon his back.

Hemiplegic, he would now slowly open his right eye to join his left, which was now almost always permanently open. He would also offer pungent, sarcastic and terse comments on the politics and the sport of the day.

His wife Rae would bring him breakfast in the nursing home across the road and wonder which of the rooms would be her’s at some time in the future.

But she was lucky, she skipped out early, confounded by a brain aneurism on the sunny North facing front verandah which was open to the air and also sheltered at the Eastern and Western ends with glass, wisteria and louvres. Every day a son would pick my father up, and take him out of his bed in the nursing home and take him home.

While confined to bed watching the television John Howard and the One Nation Party particularly drew his wrath. In earlier times Bob Hawke had earned his wrath as a “broken straw” after his proposal for a $5 fee to access a doctor under a service that the government under P.M. Whitlam and then Fraser had previously indemnified as free. Fortunately Bob was done like a dinner on that one. My father liked PM Keating, maybe it was his black irish tongue, maybe because Keating’s uncle as a soldier had died on the same sodden ground over which he had tread; and where en route to his reporting to his senior officer my father found him on the battlefield “as dead as a door-nail.”

On the death of the Princess Diana, the old hemiplegic doctor counselled a shocked tea lady at the nursing home at which he was now a patient: “It’s no worse than the fate of any of a dozen young women who die the same way in Ipswich every year!” he reminded her.

But on this particular day in 1997 my father first went to his bedroom. The big, Queen sized bed was flanked, as it always had been, for the benefit of we children as much as for himself and his wife, by two framed prints;

Titian’s Madonna and Child, also known as the Cowper Madonna on one side, and Michelangelo’s red chalk drawing of a Madonna and eager Child on the other.

Strangely, throughout my life, I’d never ever heard my father speak of either his mother or his father.

On this particular day in 1997 my father noticed a blue and white plastic statuette containing holy water from Lourdes that his only daughter Jeanie had left on his wife’s red cedar dressing table before returning to France. He quickly advised me, his orderly for the day, “You’d better get rid of that! One of the patients might come in and think I’ve gone into practising voodooism!”

Not all the burden of his behaving as the good doctor with a commitment to science had been lifted from him on this particular day.

Later that day, which I feel compelled to tell you about, dear A, (after all you are a musician with the most excellent ear), the good old retired doctor of sixty years experience and practice in the art of medicine found himself eating a dessert of lychees, sweet Vietnamese beans, syrup, jellies and cocoanut cream, garnished with crushed peanuts and ice. It was his dessert after he’d finished his main course of sticky rice and sweet ginger chicken that my wife the new bride had prepared for him.

My father was watching his favourite musical variety show; The Nat King Cole Show, broadcast again in black and white. It was a far less scratchy print, and a far less snowy screen than when he had first watched the faultless Nat on a black and white t.v. in the 1960s some thirty or more years before.

Perhaps, as he sat musing the programme, he was recalling the black Americans he had fought beside in New Guinea, at Gona or on Tarakan or on the island of Morotai fifty odd years before. He may have watched these men in army boxing matches and maybe some had invited him to hear their playing of the blues. Maybe he was remembering a medic or a patient from all those years ago. Perhaps he was recalling his childhood friends in Alpha in Central Western Queensland or others who he missed from a long long time ago.

Perhaps he was just luxuriating in the tunes of Nat, Harry Belafonte, and Nelson Riddle’s strings. Perhaps Ben E King had just sung “Spanish Harlem” “There is a rose in Spanish Harlem … There is a rose so sweet …in Spanish Ha-ah-ah-arlem …”

Maybe Josh White had sung and played “Lord well I wonder will my mother be on that train? I wonder will my mother will be on that train?”

He glanced up at his dear number 4 son, who he estimated a pretty brave and slightly daring fellow while not completely chock a block with intellect, or dexterity and whom he now most valued as a caring and dedicated nurse. He knew that 40 years previously, his maternal grandmother had dissed this son by referring to him as one of a “Pack of Savages” and a “bold brazen serpent” .

He also looked at the author of his wonderful meal, his son's brown skinned spouse. The colour of his wife’s soft brown skin was not unlike the colour of the soft, tan leather that was his own outer membrane.

Shera kids and carer Alpha central Western Queensland circa 1917

As happy as a cat in cream, emboldened by the music he loved and the wonderful cuisine, he whispered confidentially, with his soft, sometimes insensitive, black irish tongue to his dear No 4 son:

"Poor old Mrs Berry, she didn’t like the blackfellas much.”

I smiled, happy that the old man enjoyed his lunch and my wife’s cuisine and the sweet music of soul and blues. I was happy that my father could share a little bit of gallows humour with me, and make light of the memory of our sometimes difficult relationship with my grandmother who the family referred to as “Gargie”.

Another day, in the garden, my father had told me that he didn’t know why crows were so maligned. He felt the Torresian crow, a different bird to its single caw, southern cousins of the Snowy High Plains, had quite a nice voice. He felt they could hold intelligent conversations with a variety of clicks, croaks crawks, caws and calls. As well as that, he posited, they did a good job cleaning up all the rubbish on the road.

Some time later on a different day, when he long been laid flat, on his hospital bed the old man was to close his great left eye for the last time and cease his scouring gaze.

His eye closed and he submerged into the depths quietly; like a great old crocodile; quiet beneath the water; never to rise again. Paul Robeson sang a beautiful tune; “Old man river, that old man river he just keeps rollin …” “He must know something…”

Post Script my Dear L , It was nice to walk with you and your mother to look at the horses in the paddock the other day! There I knew it! She and my great Uncle McKelvey worked together at the Alfred Hospital in the 1930s! And of course both of our parents worked at the same medical mill in Queensland after the war.

And so sad the tragedy of your mum losing her first husband on the torpedoed Hospital Ship the Centaur. That ship that could easily have been carrying my dear old dad or yours and I am sure carried some of their medical colleagues and comrades.

Oh the naked tragedy, waste and folly of war!

But then, of course, there was you; a difficult birth I hear. LOL.

Love to yo on the road..

PPS Sorry to tell you that your friend, my dear old dad has left the carnival, the carnival that he was so keen to be a part of every single day; until his last.

Sometimes he comes to see us; in the very best tradition, as a canny, clever old crow. Sometimes mum comes too! Sometimes as clever old Crow 2, but mostly as a superb blue wren or a delicate, aqua butterfly.

And you my dear dear readers, May the road rise with you!